Have you seen those memes where cruel Pythonistas try to seduce naive Java/ C++ developers? Do the programmers in your team also clump together based on language? Are you curious what are the origins of this ancient battle? In the following articles, we’ll know the position of every side and maybe join the one.

This article is written by Ilya G. who aims to give some perspective on why Python is so popular today and why it is worth your time and effort even if it is not your currently used programming language.

Author’s background:

- Programming experience – 6 years

- Current position – lead Python developer at a product company

- Languages used in production and for personal projects

○ Java (8+)

○ Scala (2.12)

○ C(98) and C++(11)

○ Matlab and Wolfram Mathematica

○ Kotlin (1.3)

○ C# (6.0)

○ CPython (3.5+), of course

○ IronPython (better to forget this experience)

DISCLAIMER: The article will also briefly overview the “good”, the “bad” and the “ugly” parts of the Python programming language.

It contains personal opinions and is not proposed as a single source of truth.

The “good” Python

Readability and syntax

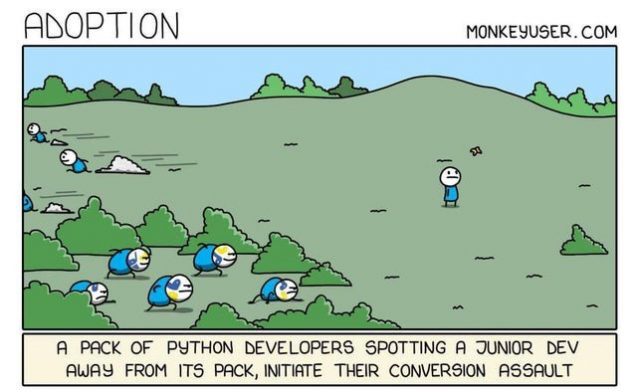

To start with, Python is meant to be readable and concise. We all should keep in mind that most of the time a programmer is reading code and not writing it. And the author’s favorite citation he found on the Internet:

“When I need to solve a task with Python, I open the editor and write some distorted English – somehow it works”

Such a feature is leading to a lower entry threshold for newcomers compared to other languages and many mature developers can confirm that with Python they write less to express more. It can be a minus though but we will cover it later.

(The author knows about StringBuilder(str).reverse().toString(), don’t throw exceptions stones at him)

Versatility and Fun

Python is quite versatile in several ways. First of all, it is a multi-paradigm programming language. You want to write in an object-oriented style – you can. Want to write in a functional style – no problem. Or, maybe, you have a great idea for the library that would require metaprogramming – go ahead and implement it!

The second part of versatility is Python’s cross-domain nature that was built by the amazing community. The author has heard many times that Python is a language with “batteries included” and agrees with this statement. The amount and quality of available open-source libraries for almost any purpose are amazing. Python itself was designed to be modular and, as a result, produced prosperous tooling. The tooling includes not only the modules that provide the functionality to build the application but also the possibilities to make your developer’s everyday life easier: linting, formatting, dependency management, testing, and more. In other words, everything the modern language needs. The number of application domains is growing and the examples are in no particular order:

- Web applications

- Data Science/Analysis/Engineering

- Systems administration

- Gamedev

- IоT

- and more…

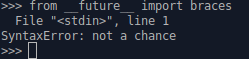

Thirdly, it is fun. Yes, really. The language is even named as a tribute to Monty Python. There are easter eggs built into the interpreter, gotta find ‘em all:

Business and Time To Market

Well, there is an illustrative story from one hackathon where the author took part. The aim of the event was, as usual, to build something valuable in a short amount of time. And there were two teams (4 people each) near the author: one chose Java for their idea and the other chose Python. The “Py” team started implementation from the architecture sketch 10 minutes after the start and came up with a working MVP 48 hours later. The “Java” team spent 2 hours only on building configuration. When the pitch time came they had only 40% of the planned functionality.

Some citations about the topic found somewhere on the internet:

“For the same task that would require 3 Java devs and a month we had 1 Python developer, same level, and one week. The task was done successfully by the last”

“You can spend 10 hours writing a neural network in C++ to make it train in 10 minutes just to find out that your hypothesis is not working. Or you can spend 10 minutes on the same task using Python and 1 hour train time to get the same result. What to do is up to you.”

Of course, these examples do not make Java or C++ less valuable. But when you need to test a product idea and a tight deadline – Python can become your savior. Even if the product fails, you spend less time and, consequently, money on it.

The “bad” Python

The cost of convenience – speed and memory consumption

“There are no zero-cost abstractions” and “Each abstraction must provide more benefit than cost”. The convenience is usually built around abstractions, abstractions require both CPU time (speed) and data (memory) to be properly processed. Python sacrificed both speed and memory in favor of convenience. In the author’s opinion, time and successful use cases have proven that the benefit is worth the tradeoff.

Although, you should keep the limitations in mind. It is not advised to use Python in some spheres, such as real-time embedded systems. For performance-critical projects compiled languages such as C/C++/Java/insert-your-compiled-language-here may be more suitable. To advocate Python, there are ways to circumvent its flaws. For example, the common practice is to write the parts that require high performance in C and use them inside your Python code. This, of course, requires additional steps and, in some cases, a significant amount of boilerplate. If this approach scares the reader, do not be afraid, the libraries usually have everything inside and give you a pretty Python frontend to be used, some of them, such as NumPy, became “de-facto standard” in production.

Lower entry threshold – the temptation to skip details

You write your first print(“Hello world”), run it, and, given that it is the first program in your life, start to feel the power to control the computer on the tip of your fingers. Time passes, you have written some scripts, (superficially) read some books, used some libraries, and achieved results. The next milestone is THE PROJECT. At work or for personal interest, something big and functional.

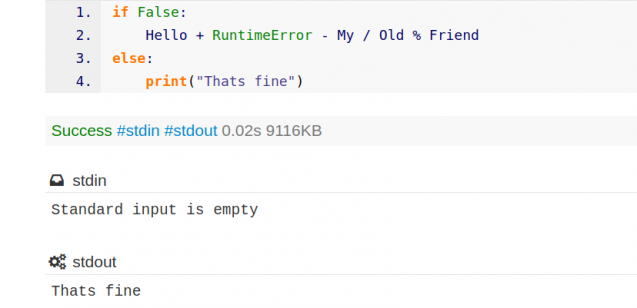

Here comes the point where you either have a mentor or gain experience the hard way. Python can “byte” you back in several aspects, and the most common are:

- GIL – threaded parallelization is slower on computation tasks than not having it

- Interpreted dynamic language – brace yourself, RuntimeErrors are coming (or not, depends on execution path)

There are strategies and tooling to mitigate the pain and gain confidence though. They are not so different from the other languages. Use static analysis tools, type annotations, write tests, spend time experimenting (preferably, not on production servers c: ), read the documentation, and learn the pitfalls. Do not hesitate to ask colleagues, if possible.

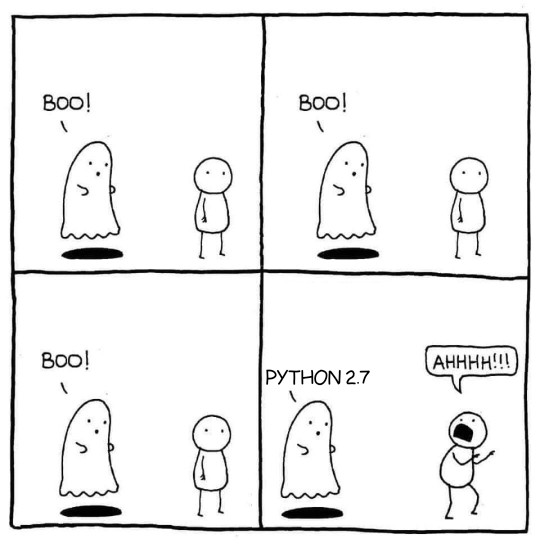

Python 2.7 is (not) dead

Several years after the release of Python 2, the developers realized that they need to change the language significantly to make it better. They started to work on Python 3 and planned the end of life for Python 2. The adoption problem appeared and messed up the plans. Many companies including such giants as Google already had huge codebases of Python 2 and the open-source libraries were not ready. The end of life was moved to January 2020 and the support for Python 2 was finally dropped. А little sad but happy ending. Or not…

Here comes the business: if something works, why should we rewrite it and spend resources? There are still projects that require support and development with the old version. Working on such projects is hard and the migration process may be frustrating.

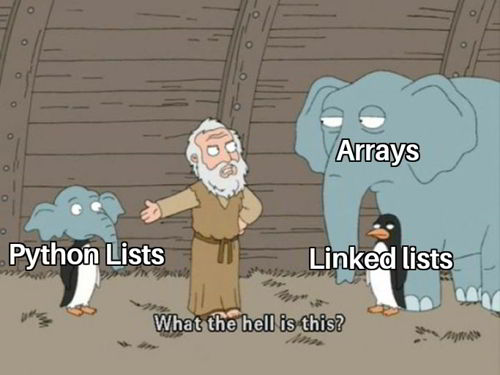

The “ugly” Python

There are design decisions in Python that are, well, questionable. Meme instead of thousand words:

There are people that “hate” Python because of its architectural nuances, insisting on “mixed paradigms and none are implemented properly” and other points. Some people have no problems using the language even knowing the flaws. Which side to support or not to support any is your choice. But remember: some tasks are solved and profits are made.

So why python?

Let’s examine a few plain facts at last: Python became the second most popular programming language according to the TIOBE index in June 2021. The first version was released in 1991 (earlier than Java) and the language is considered mature. The language has chosen the slow but steady path to gain its popularity, unlike Ruby, for example, which had its peak when the Ruby On Rails framework was new and popular. There is enough space to grow further and the developers of the language are constantly working on new features to make it better. The changes proposed are going through the long but necessary process of polishing and the Python 2 to 3 migration disaster is unlikely to happen again. Moreover, Python listens to the end-users – us, the developers, and tries to adopt features that were proven to be useful in other languages.

The author genuinely hopes the article has helped someone get a better overview of Python, keeping it brief and without too many technical details.